Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Vaudevillian Dialectic

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Kantian Links

Here are some links related to Immanuel Kant's theory of ethics:

- An intermediate overview of Kant's theory of ethics.

- An advanced overview of Kant's ethics.

- Kant's theory is deontological (which is a fancy word that basically means morality is about more than just the consequences of an action). Here's an advanced overview of deontological ethics.

- Some harsh criticisms of Kant's ethical judgments. My favorite excerpt: "Kant's philosophical moral reasoning appears mainly to have confirmed his prejudices and the ideas inherited from his culture. Therefore, we should be nervous about expecting more from the philosophical moral reasoning of people less philosophically capable than Kant."

- A 3-minute video on Kant's ethics is below:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

kant,

links,

videos

Friday, September 23, 2011

Group Presentations

Here are the groups for your consensus session presentations, along with the date of each presentation, the due date of your email, and the article your group is assigned to:

Embyronic Stem CellsIf your name isn't on this list, please let me know as soon as possible so we can figure out what group you're in.

-Group 1 on October 26th (email due October 19th): Hyan article – pages 316-319: Christopher, Dana, Kendal, Megan

-Group 2 on October 28th (email due October 21st): Magill & Neaves article – pages 319-323: Brittney, Danny, Gabi, Phi

Genetic Control

-Group 3 on November 2nd (email due October 26th): Davis article – pages 285-294: Lakeisha, Melissa, Sangsu, Shanice

Cloning

-Group 4 on November 4th (email due October 28th): Kass article – pages 401-406: Alyssa, Avery, Eric, Potsy

-Group 5 on November 7th (email due October 31st): Strong article – pages 406-411: no one

Homosexual Parenthood

-Group 6 on November 9th (email due November 2nd): Hanscombe article – pages 406-409: Hannah, Leigh, Rhea, Robyn

Impaired Infants

-Group 7 on November 14th (email due November 7th): Engelhardt article – pages 543-548: no one

Euthanasia

-Group 8 on November 18th (email due November 11th): Callahan article – pages 596-600: Kelly, Marissa, Nick S., Tamara

-Group 9 on November 21st (email due November 14th): Rachels article – pages 585-589: Andrea, Ashley, Kim, Shana

Animal Research

-Group 10 on November 30th (email due November 23rd): Cohen article – pages 203-209: Greg, Joe, Lauren, Nick D., Tiffany

Race and Gender

-Group 11 on December 5th (email due November 28th): Dula article – pages 798-894: no one

The Economics of Health Care

-Group 12 on December 9th (email due December 2nd): Daniels article – pages 713-716: Becky, Lorraine, Mark, Pinky

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

consensus,

logistics

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

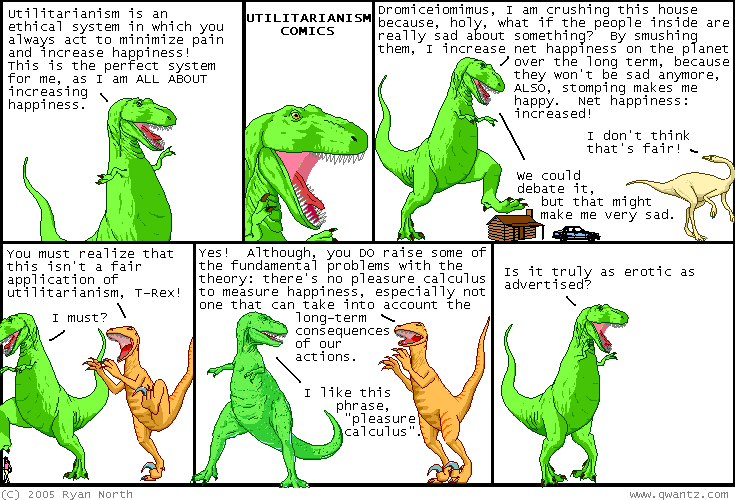

The Psychology of Happiness

Since utilitarianism focuses so much on happiness, I thought I'd share some links on the cool new psychological research on happiness popping up lately.

- Here's one overview of the psychology of happiness. And here's a second one.

- Recent studies suggest that our baseline level of happiness doesn't change much throughout our life. So, even if we won the lottery, we wouldn't wind up that much happier. This is potentially very depressing news, although some say there's room for some optimism, and others think the research is wrong.

- There's an insightful, accessible book by Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert called Stumbling on Happiness. One of his big points is that we often don't know what makes us happy. Here's Gilbert's appearance on The Colbert Report:

- And here's Gilbert giving an awesome TED talk on his research:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

links,

utilitarianism,

videos

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Utilitarios!

Here are some links on the theory of utilitarianism:

- A neat little biography of know-it-all John Stuart Mill

- An advanced encyclopedia article on utilitarianism and other theories that focus on consequences of an action.

- The trolley problem gets brought up a lot when evaluating utilitarianism. A short video intro on it is below. Also, there's some new research on the psychology of the trolley problem.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

links,

utilitarianism,

videos

Monday, September 12, 2011

Evaluating Arguments

Here are the answers to the handout on evaluating arguments that we did as group work in class.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.

All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

P1- true

P2- true

support- good

overall- good

2) All email forwards are annoying.

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

P1- questionable ("annoying" is subjective)3) All males in this class are humans.

P2- true

structure- good (the premises establish that some email forwards are both annoying and false; so some annoying things [those forwards] are false)

overall - bad (bad first premise)

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

P1- true4) No humans are amphibians.

P2- true

support- bad (the premises only tell us that males and females both belong to the humans group; we don't know enough about the relationship between males and females from this)

overall- bad (bad support)

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

P1- true5) All bats are mammals.

P2- true

structure- good (the premises say that frogs belong to a group that humans can't belong to, so it follows that no frogs are humans)

overall- good

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

P1- true6) Some dads have beards.

P2- true (if interpreted to mean "All bats are the sorts of creatures who have wings.") or false (if interpreted to mean "Each and every living bat has wings," since some bats are born without wings)

support- bad (we don't know anything about the relationship between mammals and winged creatures just from the fact that bats belong to each group)

overall- bad (bad support)

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

P1- true7) Oprah Winfrey is a person.

P2- questionable ("mean" is subjective)

support- good (if all the people with beards were mean, then the dads with beards would be mean, so some dads would be mean)

overall- bad (bad 2nd premise)

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

P1- true8) All students in here are mammals.

P2- true (you might not have directly seen anyone eat tacos, but you have a lot of indirect evidence... with all the Taco Bells, Don Pablos, etc., surely lots of people ate tacos yesterday)

support- bad (the 2nd premise only says some ate tacos; Oprah could be one of the people who didn't)

overall- bad (bad support)

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

P1- true

P2- true

structure- bad (the premises only tell us that students and humans both belong to the mammals group; we don't know enough about the relationship between students and humans from this; for instance, what if a dog were a student in our class?)

overall- bad (bad structure)

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

P1- true!10) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

P3- questionable ("scary" is subjective)

structure- good (same structure as in argument #1, just with an extra premise)

overall- bad (bad 3rd premise)

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

P1- questionable (since you haven't heard me sing, you don't know whether it's true or false)11) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

structure- good

overall- bad (bad premises)

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)12) All students in here are humans.

P2- true

structure- bad (from premise 1, we only know what happens when Sean is singing, not when he isn't singing; students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- bad (bad 1st premise and structure)

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

P1- true13) (from Stephen Colbert)

P2- true!

support- so-so (the premises state a strong statistical generalization over a large population, and the conclusion claims that this generalization holds for a much smaller portion of that population; while it could be true that the humans in here are a statistical anomaly, given the strength of the generalization, it's likely that most students in here are, in fact, shorter than 7 feet tall)

overall- so-so (not perfect, since the support isn't perfect, but pretty good)

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

P1- questionable ("great" is subjective)14) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- questionable ("great" is subjective)

support- good (it's either A or B; it's not A; so it's B)

overall- bad (bad premises)

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)15) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

structure- bad (from premise 1, we only know that Sean singing is one way to guarantee that students cringe; just because they're cringing doesn't mean Sean's the one who caused it; again, students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- bad (bad premises and structure)

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)16) If there is no God, then life is meaningless.

P2- true

structure- good

overall- bad (bad 1st premise)

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

P1- questionable (that's not an obvious claim to prove or disprove)

P2- questionable (again, that's not an obvious claim to prove or disprove)

support- good (the same structure as argument #13)

overall- bad (bad premises)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

links

Quiz #1

Just a reminder that our first quiz will be held at the beginning of class on Wednesday, September 15th. It's worth 50 points (5% of your overall grade), and will be on understanding and evaluating arguments. The quiz will look a lot like the extra credit handout (on understanding arguments) from last week, and the group work handout (on evaluating arguments) from Monday.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

logistics

Sunday, September 11, 2011

An Argument's Support

One of the trickier concepts to understand in this course is the structure (or support) of an argument. This is a more detailed explanation of the term (it's the same as the handout). If you've been struggling to understand this term, the following might help you.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Friday, September 9, 2011

That Beyoncé Video WAS Great...

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

links,

videos

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Howard Sure Is a Duck

Howard the Duck is my favorite synecdoche for the 80's:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

videos

Monday, September 5, 2011

Philosophers In Their Own Words

Photographer Steve Pyke has a cool series of portraits of philosophers. Many of the philosophers also provide a short explanation of their understanding of what it is they do. Here are a few of my favorites:

Delia Graff Fara:

Delia Graff Fara:

"By doing philosophy we can discover eternal and mind independent truths about the ’real’ nature of the world by investigating our own conceptions of it, and by subjecting our most commonly or firmly held beliefs to what would otherwise be perversely strict scrutiny."

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):

Delia Graff Fara:

Delia Graff Fara: "By doing philosophy we can discover eternal and mind independent truths about the ’real’ nature of the world by investigating our own conceptions of it, and by subjecting our most commonly or firmly held beliefs to what would otherwise be perversely strict scrutiny."

"Philosophy is the strangest of subjects: it aims at rigour and yet is unable to establish any results; it attempts to deal with the most profound questions and yet constantly finds itself preoccupied with the trivialities of language; and it claims to be of great relevance to rational enquiry and the conduct of our life and yet is almost completely ignored. But perhaps what is strangest of all is the passion and intensity with which it is pursued by those who have fallen in its grip."

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):

Sally Haslanger (only available in the book):"Given the amount of suffering and injustice in the world, I flip-flop between thinking that doing philosophy is a complete luxury and that it is an absolute necessity. The idea that it is something in between strikes me as a dodge. So I do it in the hope that it is a contribution, and with the fear that I’m just being self-indulgent. I suppose these are the moral risks life is made of."

Friday, September 2, 2011

Philosophy: The Annoying 3-Year-Old

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

videos

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Kit Fine

Kit Fine